Integrating natural capital into economic reporting

Gross Domestic Product has for decades served as the preeminent system of measurement for a country’s economic activity...

Bernhard Obenhuber

Apr 13, 2021

Gross Domestic Product has for decades served as the preeminent system of measurement for a country’s economic activity after the System of National Accounts adopted it in 1947 as the primary statistic. But over time and due to a lack of better alternatives, GDP has been abused as the measuring stick of a country’s economic size, wealth, and growth rate. A fallacy has emerged that faster growth meant more wealth overall for a country and also higher level of welfare & wellbeing for each citizen.

Today, GDP growth continues to be equated with welfare gain, despite the system never actually being meant to measure welfare or the wellbeing of a country’s citizens. By only assessing output and without a mechanism for identifying the wealth and assets (e.g. natural capital) that underlie output and the quality of that output (think spending on cleaning up an oil spill versus school buildings) the inherent limitations of GDP as an indicator of economic performance and welfare have become apparent. This is problematic since, in its current form, GDP does not account for permanent or significant depletion or replenishment of natural assets. Ultimately, this means GDP has no capacity to identify whether the level of income generated in a country is sustainable.

Several shortcomings as a measure of welfare

A closer look at the structure of GDP reveals further flaws in its role as a proxy for the welfare of a country’s citizens. For instance, countries with a large informal economy or with a large volunteer system may record lower economic output. By shifting volunteer work, such as a fire brigade, to a paid service provider, GDP correspondingly goes up. The same is true for all the unpaid but important work people do to care for family members. These omissions limit the quality of GDP as a measure of welfare of a country.

Rethinking GDP by incorporating nature and sustainability into calculation

Much economic activity is directly dependent on nature — the World Economic Forum has calculated that around $44 trillion of GDP, more than half the global total, is moderately or highly dependent on natural systems. It also underpins our health and wellbeing (see The New Nature Economy Report here). However, natural capital is poorly represented in GDP. Since there is no recorded monetary cost of the creation of natural assets, such resources anot adequately considered as economic assets. When the current system of national accounts was conceived, the availability of natural assets was plentiful relative to humanity’s use of them. This made them appear as free goods. Although that reality has dramatically changed since, inertia and path dependency has led to an unmodified application of national accounting.

Important positive externalities that arise from natural capital, such as forests and wetlands, are unaccounted for or otherwise hidden because of practical difficulties around measuring and pricing these assets. Similarly, the impact that the degradation of natural resources or increases in pollution can have on the future productive capacity of a nation are currently unaccounted for in GDP estimates. As a result, if natural capital continues to be seen as “free”, the benefits that nature provides will be taken for granted and used at a rate that the earth cannot replenish.

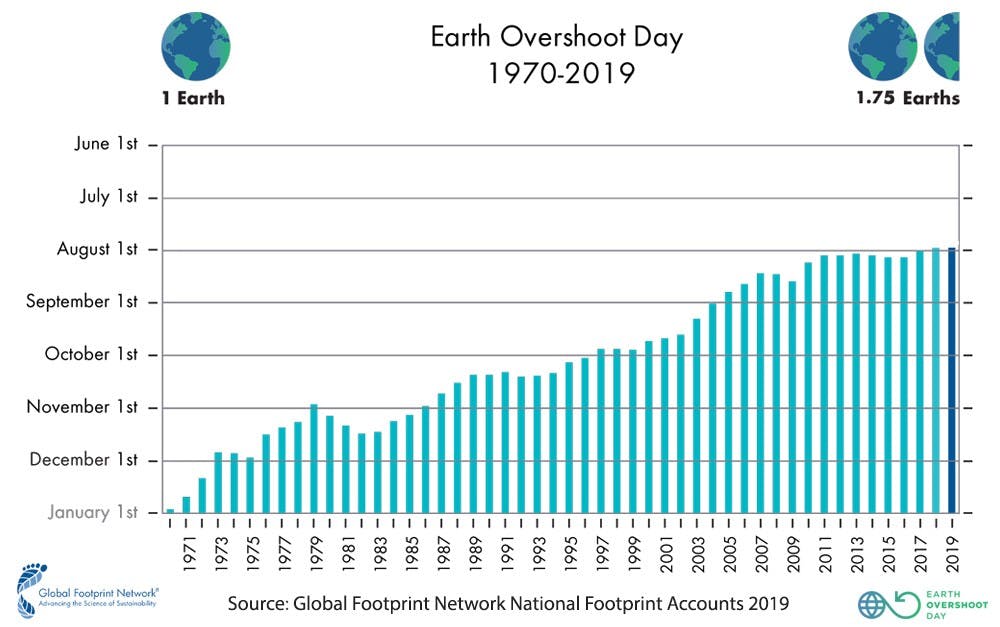

The “Earth Overshoot Day” indicates the day of each year when the humanity’s demand for ecological resources exceeds the regeneration capacity. Since the early 70s, this day has been earlier and earlier. Even in 2020, when the world was in the grip of a deep economic recession that “World Overshoot Day” fell on August 22.

Consequently, we need a system that highlights how we depend on nature.

Herculean task: taking nature into account

Natural capital accounting is one such system. It calculates the total stocks and flows of natural resources and services in a given ecosystem or region and can be expressed in monetary terms. It can be used to inform government decision making as it relates to the use or consumption of natural resources and land, and sustainable behaviour. Meanwhile, monetary estimates can provide information for governments for economic policy planning, cost-benefit analysis, and for raising awareness of the relative importance of nature to society.

A rethink of GDP is now underway with growing calls for adjusted GDP or ‘green GDP’. This systematically corrects conventional GDP by taking into account aspects of a country’s production of goods that would not otherwise be included but are relevant to sustainability, such as environmental degradation and natural resources depletion. In essence, green GDP represents the monetisation of the loss of biodiversity and also accounts for costs caused by climate change. Consequently, the argument is gaining pace that green GDP would be a more accurate indicator or measure of societal wellbeing and that the integration of environmental statistics into national accounts, and the establishment of a green GDP figure, would improve countries’ abilities to manage their economies and resources.

UN adopts landmark framework to integrate natural capital in economic reporting

Change could be on the horizon. The recent adoption of the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting — Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA) by the UN Statistical Commission may reshape policy-making towards sustainable development by including the contributions of nature when measuring economic prosperity and wellbeing. The framework answers important overarching questions on the relationship between the economy, society, and the environment, such as how taking the state of a country’s environment into account might affect estimates of its wealth and economic potential.

Currently, 34 countries are compiling ecosystem accounts on an experimental basis and more countries are expected to begin implementing the system, although a significant number will require assistance and additional resources for statistical data collection. Pioneers include Finland, which has also established the Co-operation Group for Environmental Accounts and Norway, which has established a conceptional framework for the country’s Ecosystem Accounts.

However, there are challenges to be overcome, such as making sure the data is up to date and not suffering from a long lag. At present, we are also still a long way away from having readily available SEEA EA data. Steps are being taken in the right direction, but the concept clearly needs more visibility and support from national governments. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of incentives for a government to switch to an accounting framework like the SEEA EA.

How we incorporate natural capital into CountryRisk.io

At CountryRisk.io, we view management of a country’s natural capital as an important indicator of sovereign risk, both in environmental and economic terms, since natural capital is typically seen as an asset on a country’s balance sheet. Furthermore, a country’s success in stopping degradation of its natural resources can also be viewed as a measurement of the quality of its governance. Thus, we believe that a government’s preservation of natural capital under the SEE EA framework will represent a new, qualitative factor that will bear on its sovereign ESG rating.

For CountryRisk.io, ESG is the new standard, and the state of a country’s natural capital indicates environmental and governance performance and the well-being of the resources its economy relies on. We have long advocated for pushing GDP to incorporate a sustainability calculation. On our platform we have already taken measures to incorporate the Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s SDG Index and we also integrate several aspects of the quality of spending and assessments of the usage of natural resources (CountryRisk.io Rating Methodology).