Running the numbers on environmental crime

Environmental crime is a global scourge...

Bernhard Obenhuber

Nov 25, 2020

Environmental crime is a global scourge. According to Interpol, it costs between $91 billion and $259 billion each year. That makes it the fourth largest criminal activity in the world, after drug smuggling, counterfeiting and human trafficking.

It includes the illegal trade in wildlife products, including timber and endangered species, inappropriate management and dumping of waste, trade in banned chemicals, and habitat destruction, among other things. As one of the so-called predicate offences that generates dirty money, understanding exposure to environmental crime is an important element of anti-money laundering (AML) compliance. But the issue should also be considered by ESG asset managers when thinking of buying sovereign bonds and as a topic of investor engagement with governments.

Indeed, the prominence of environmental crime was highlighted as we are currently in the process of our regular CountryRisk.io AML model review. We thought it would be timely to dig into some of the challenges analysts face in understanding exposures to environmental crime — and some of the insights that can follow from a better understanding of the issue.

Rising up the agenda

Certainly, there is a growing number of international efforts to tighten up on environmental crime. In 2003, the EU introduced the EU Timber Regulation, which requires companies selling timber and timber products in the EU to ensure the timber was legally harvested.

In the US, the Lacy Act dates back to 1900, but it was amended in 2008 to include plants and plant products, banning trade in illegally sourced wood products. The most far reaching is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) from the early 1970s.

Regulatory tightening continues. Switzerland is debating holding a referendum on a Responsible Business Initiative. It would require multinational companies operating in the country to address negative social and environmental impacts throughout their supply chains and to apply Swiss social and environmental standards to their overseas operations.

Challenges with the data

However, understanding where the risks of environmental crime are greatest can be challenging. There are a number of international databases that provide at least partial clues. But getting a holistic picture about environmental crimes and cross-border flows is not possible at this point in time. For this blog post, we zoom in on a specific area of environmental crime: the illegal trade and trafficking of wildlife.

Set up under the auspices the treaty, the CITES Trade Database is an impressive database that collects information on legal and illegal wildlife trade activities since the 1970s and has a well-established reporting mechanism.

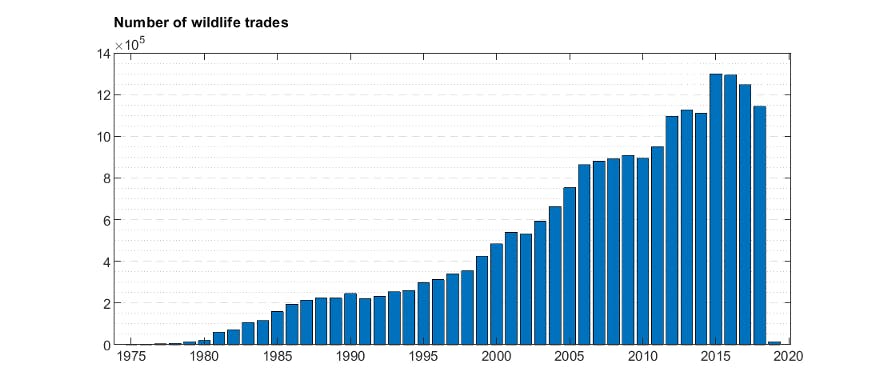

In 2019, there were more than one million trades registered that involved protected species as defined in the convention; think elephant tusks, living reptilia or timber from protected species. In total, the CITES database contains more than 23 million records.

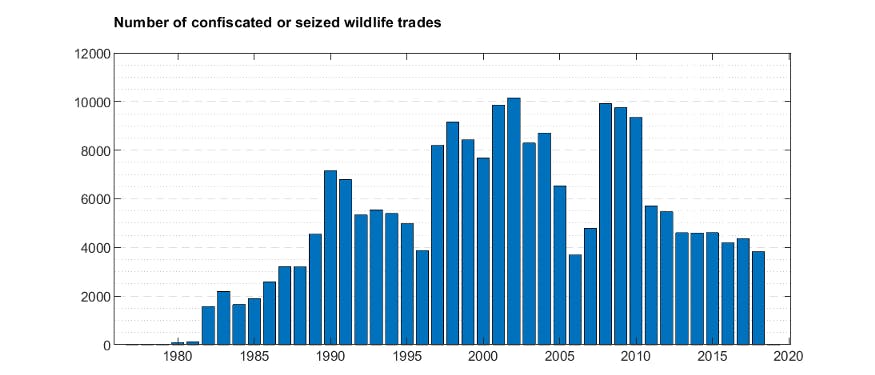

Out of this large number, there are around 4,000 trades per year confiscated or seized by customs, accounting for around 1% of the total. Of course, the actual illegal activities are difficult to quantify and are probably much higher.

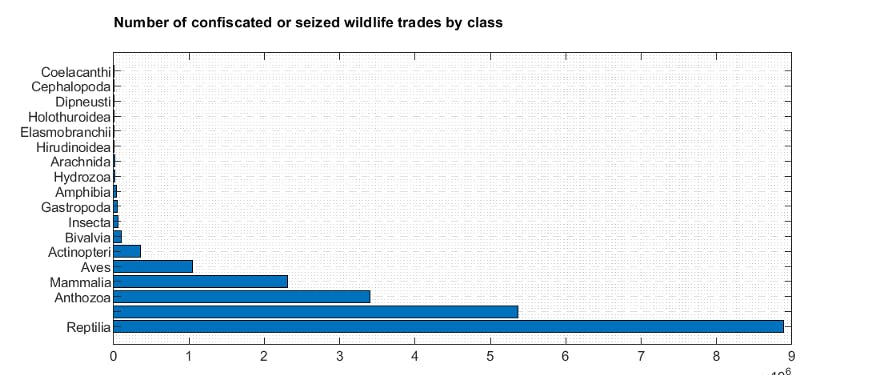

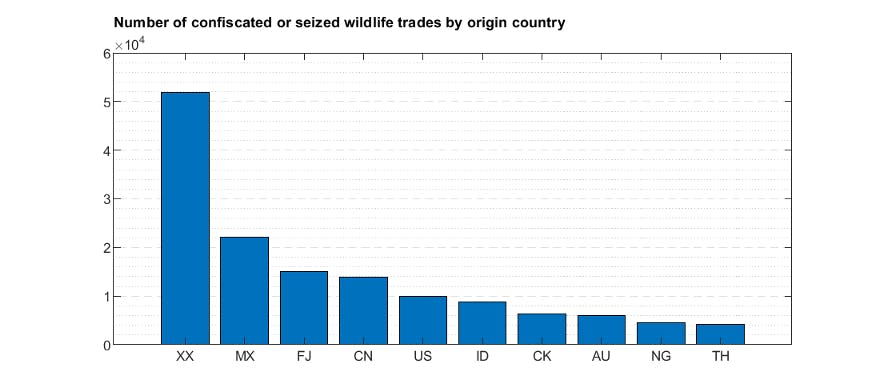

Reptiles make up the majority of confiscated wildlife, followed by a large number of unidentified items and Anthozoa (corals). A lack of information is also apparent if one analyses the data by country of origin. The top 10 countries are shown below. The first one, “XX”, identifies trades where the country of origin is unknown; followed by Mexico, Fiji, China and the US.

The CITES database is a great source of information to begin to better understand illegal trade activities. However, one should be careful with interpretation and the drawing of conclusions. As always, in order to count a crime, one needs to uncover it first. In the context of cross-border trade, this requires wellresourced and well-trained customs personnel. This is often a problem in the context of regional trade (e.g. within neighbouring countries of Africa or Southeast Asia).

As a result, evidence of environmental crime can be evidence of good governance rather the opposite. Jurisdictions with porous borders and little scrutiny of what goods pass across them will likely collect little evidence of illegal wildlife and timber smuggling, for example.

How we incorporate environmental crime data into CountryRisk.io

As mentioned above, we conducted this deep dive into wildlife trafficking in the context of the upcoming AML model review that will include a separate risk section on the prevalence of various predicate offences (e.g. drug smuggling, human trafficking, cyber-crime, etc.) as outlined in the EU’s Sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive. We plan to integrate some of the wildlife trafficking data and visualisations into the platform to help AML country analysts to better understand where dirty money might be coming from. Similarly, we will consider adding an indicator to the ESG sovereign risk rating model regarding a country’s strength of enforcement of international conventions.

For more information on our AML model review, please reach out to us at [email protected].